Contributed by Fidelis Onwuagba, 2023 GSA Graduate Student Research Grant recipient

Access to clean and safe drinking water is something many of us take for granted, yet the quality of groundwater can be strongly influenced by the rocks it flows through. During my master’s research at Kansas State University, I set out to understand how geology, specifically the presence of organic‑rich shales, can influence groundwater chemistry and raise potential health risks in southeastern Kansas.

This piece shares the story behind that research: why it matters, what we found, and what it means for communities that rely on domestic wells.

Why Study Uranium and Trace Metals in Groundwater?

Uranium is a naturally occurring element found in many rocks, particularly organic‑rich sedimentary rocks such as black shales. Under certain geochemical conditions, uranium can dissolve into groundwater and become a drinking water concern. While uranium contamination is often associated with mining or other human activities, less attention has been given to natural water–rock interactions as a source.

Southeastern Kansas provides an ideal natural laboratory for this question. The region is underlain by the Ozark aquifer (Fig. 1), a carbonate aquifer system that is in close contact with black shales and coal‑bearing units. Many rural residents in this area rely on private domestic wells, which are typically unregulated and infrequently tested. Understanding the natural controls on groundwater chemistry here is therefore both scientifically important and socially relevant.

Fieldwork: Sampling Water Across Southeastern Kansas

This study included a month‑long field campaign during which I sampled groundwater from domestic wells across Bourbon, Crawford, and Cherokee Counties. At each site, I measured in situ parameters such as pH, temperature, dissolved oxygen, and electrical conductivity, and collected samples for laboratory analysis (Fig. 2).

In the lab, these samples were analyzed for major ions and trace metals using techniques such as ion chromatography, alkalinity titration, and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP‑MS). I also compiled geophysical data, specifically gamma‑ray well logs, to map the distribution and thickness of black shales beneath the study area.

What Did We Find?

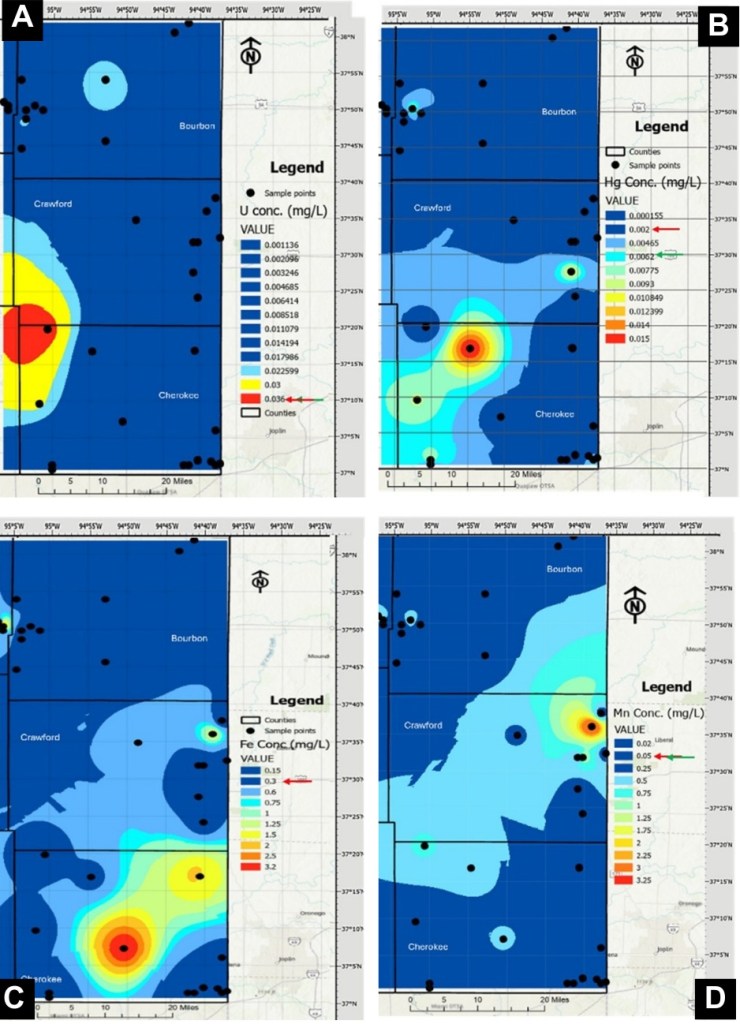

One of the most important findings of the study was that uranium concentrations in groundwater were generally low (Fig. 3a) and mostly within U.S. EPA and WHO drinking‑water standards. Despite the presence of uranium‑rich black shales, widespread uranium contamination was not observed.

However, the story does not end there. Several other constituents, including manganese, iron, and mercury, were found at elevated concentrations in multiple wells. Some of these elements exceeded recommended drinking‑water limits, posing a health threat if ingested.

Geochemical modeling (Fig. 4) and statistical analysis suggested that groundwater chemistry in the region is controlled by a combination of oxidation-reduction conditions, carbonate alkalinity, and interactions with organic‑rich rocks and legacy mining materials.

Processes that limit uranium mobility, such as adsorption onto mineral surfaces, may simultaneously allow other metals to remain mobile in groundwater.

Why This Matters Beyond Geology

Groundwater geochemistry sits at the intersection of geology, environmental science, and public health. Although uranium itself was not a concern in this study, the presence of other redox‑sensitive metals directly and indirectly linked to adverse health effects in humans in humans highlights the importance of regular water testing, especially for private well owners.

From a broader perspective, this research contributes to the growing field of medical geology, which examines how geological materials and processes affect human health. By identifying natural controls on groundwater quality, studies like this can help guide better monitoring strategies and inform water‑management decisions in similar geological settings.

Final Thoughts

Groundwater does not exist in isolation; it carries the chemical fingerprint of the rocks it encounters along its flow path. By studying these interactions, we can better understand both the opportunities and risks associated with our subsurface resources.

I hope this work encourages students, early‑career geoscientists, and the broader public to think more deeply about the hidden connections between geology and everyday life, especially the water we drink. This research was supervised by Dr. Karin Goldberg, associate professor at Kansas State University.

Author Bio

Fidelis Onwuagba is currently a PhD student at the University of Kansas, where his research has expanded into understanding how critical minerals, particularly rare earth elements, can be mobilized from black shales using supercritical CO₂. These elements are essential components of modern technologies that support the global energy transition, including wind turbines, electric vehicles, energy-efficient electronics, and advanced battery systems.

By investigating alternative and potentially lower-impact ways to extract rare earth elements from unconventional geological materials, his current work aims to contribute to a more secure and sustainable supply of these critical resources. In this sense, his research builds directly on the same theme that motivated his master’s work: understanding fluid–rock interactions not only to protect water resources, but also to responsibly support the materials needed for a cleaner energy future.