Contributed by Nowell Donovan (Provost Emeritus, Texas Christian University), Robert Gatliff (Edinburgh Geological Society) and Colin Cambell (CEO, The James Hutton Institute)

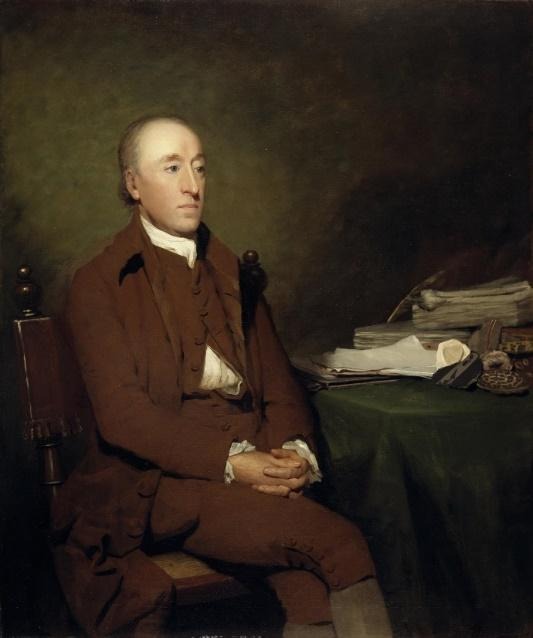

In the second half of the eighteenth century, Edinburgh was at the center of the “Scottish Enlightenment,” an extraordinary community of brilliant folk that included David Hume, possibly the greatest philosopher ever to write in the English language; Adam Smith, arguably the world’s greatest economist; Joseph Black, chemist and discoverer of CO2; Adam Ferguson, the first sociologist; and James Hutton. These five, together with many more, were companions who corresponded frequently and socialized with joy, especially in the (in)famous Oyster Club. Part of the magic they created was that they all understood and enjoyed the breadth of each other’s expertise.

The flair of the Scots in the development of our collective knowledge was widely recognized in Europe and America. Thomas Jefferson, himself a man of the Enlightenment, wrote, “So far as science is concerned, no place in the world can pretend to competition with Edinburgh.” Ben Franklin who visited Scotland twice, in 1759 and 1771, recalled his earlier visit to Edinburgh as “the densest happiness” that he had ever experienced. The Scots reciprocated—Franklin was the first foreigner elected to the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

Hutton was a true polymath: in addition to being a medical doctor and a farmer who brought new ploughing techniques to Scotland, he also studied crops, including the latest varieties of potato and developed the use of lime to improve soils. He measured the effect that altitude has on temperature and developed a theory of rain. He completed his education in Paris (where he probably received a geological education) and Leiden. He was also a successful chemist and businessman with a factory in Edinburgh making sal-ammoniac (aluminum chloride), which was used in dyeing. He used his geological expertise in the construction of the canal that links Edinburgh and Glasgow.

He authored the first two volumes of A Theory of the Earth—a third volume was published posthumously. In addition, he wrote a three-volume treatise titled The Principles of Knowledge. A hitherto unpublished Treatise on Agriculture will be published this year as part of the Hutton Tercentenary Celebrations.

It was during his years as a farmer in the south of Scotland that he developed his geological ideas from studying the land around his farms. He recognized that the soils were gradually being eroded by wind and rain and more soil formed from the rocks and organic matter. This was a slow process. He also recognized that the bedrock was made of two types of rock: the schistose and the red sandstone. Both were made of sand grains eroded from older rocks during the slow process of soil formation and erosion. He deduced that the schistose was harder and more deformed and that the red sandstones were younger and less deformed. His theory was that the schistose had been buried, heated, turned into rock, and folded, uplifted, and eroded—hence new sand formed— and was later buried, heated, turned into rock, and uplifted and eroded once more—a series of cycles with “no vestiges of a beginning and no sign of an end.” His theory needed evidence, and he deduced from mapping the two types of rock that he could find the junction. A classic, and maybe first, use of our modern scientific method!

He set sail with two friends, John Playfair and James Hall, and they found Siccar Point. This beautiful spot displayed a brilliant three-dimensional exposure of the Unconformity. Playfair said of the event that“the mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far back into the abyss of time.” This was considered the first proof that the Earth was millions or billions of years old.

Scotland has a tremendously varied geology, including granite. Existing consensus suggested that granite was the primeval rock, underlying all else and precipitated from a primal ocean. Hutton argued the converse: granite and other related rocks had once been molten and could be produced at any time in the history of the Earth. Rock exposures proving his point by demonstrating the intrusive nature of granite were located in Glen Tilt in the Highlands of Perthshire. Other exposures that proved his point were located on Edinburgh’s Salisbury Crags, where he demonstrated that microgabbroic rocks were also igneous intrusions and not precipitates from the oceans. Hutton recognized the critical role that heat played in controlling the form of the planet.

Some of you will have visited Siccar Point, as it is only 35 miles from Edinburgh, but it is not sign-posted and involves a walk across fields to the top of a steep grassy cliff, which discourages many visitors. There are some information boards, but for such a historically important site (the first to be described in the IUGS 100 most important historical geological sites volume) there is so much more that can be done. We think that with better information and better access we can use the site to promote the importance and impact of geology on our lives. The nearby village of Cockburnspath marks the end of long-distance footpaths along the coast and the end of the Southern Uplands Way, which is a geological extension of the Iapetus Ocean and the Appalachian Way in America.

To celebrate the tercentenary of Hutton’s birth, Edinburgh Geological Society has commissioned experts to put together a “Deep Time Trail” based on a series of waypoints with information about the route, the history of geology, and its impact on our lives, with information on the landscape, farming, and key geological features. We hope to get this new route to a viewpoint at the top of the cliff in place by the summer, with a further phase in 2027 to build a stairway down to the Unconformity.

When you make a qualifying donation to the project, you can receive a print from John Clerk of Eldin’s Lost Drawings from Hutton’s Theory of the Earth, generously donated by Clerk’s family, who still live near Edinburgh. To learn more about donation levels and rewards, please visit our https://www.scottishgeologytrust.org/crowdfunder/.