Contributed by Dean Wrobel, GSA Graduate Student Research Grant Recipient

Blacktop fades to gravel at the end of Highway 236 on the way to Little River Neck, a peninsula separating the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway from the waters of the Atlantic Ocean in northeast South Carolina. The washboard road winds through dense forests of live oak and pine before veering east, transitioning to a causeway barely rising above the saltmarshes of Dunn Sound, which serves as the only rugged conduit to Waties Island, South Carolina. This pristine Holocene barrier island, located at the NC-SC border, is juxtaposed by the sprawling golf and beach destination of Myrtle Beach to the south and many idyllic seaside resort towns to the north. Stands of loblolly pine tower above the saltmarsh meadows of smooth cordgrass and black needlerush, a distant reminder of the once-abundant natural heritage, now transformed into monocultures of manicured fairways and imposing highrise resorts.

Despite the surficial transformation of these landscapes, much of the underlying geology has remained undisturbed. The mainland of wave-dominated barrier islands such as Waties Island is composed of fine, primarily quartz sand, which extends to the modern-day dune and beach complex. Toward the backside of the island, the geology becomes complex. Coastal processes such as overwashing and inlet dynamics have layered large fans of this quartz sand into an otherwise muddy marsh environment. The sporadic nature of these events has created a nonhomogenous sedimentary package along the backside of the island. These different sediments, and specifically the difference in sediment porosity, has generated a mosaic of habitats along the transition from maritime forest to saltmarsh. Stands of Juniperus virginiana and Quercus virginaia rise out of the marsh grasses atop small mounds of sandy sediment. Adjacent to these small islands of trees, high-salinity saltpans support Salicornia virginica, and brackish depressions in the marsh platform abound with Juncus roemaria and invasive Phragmites australis.

The variety of ecotones is representative of the island’s complex hydrogeology, where pluvial freshwater from the island blends with brackish waters of Dunn sound and saline waters of Hog Inlet and Atlantic Ocean. This mixing of groundwaters occurs within the saltmarsh sediment package, where surface waters slowly percolate through near-impervious surficial mud, while groundwaters exchange rapidly beneath using highly permeable sand deposits as conduits. This “subterranean estuary,” as it has been dubbed by seminal researchers, has garnered increased attention in recent decades for its contribution of nutrients to the coastal ocean and enrichment of coastal ecological productivity. While the biogeochemical interactions here have become well understood in these areas, there is still much to learn about the variability in physical processes controlling the export of these nutrient rich porewaters.

Factors such as tides, precipitation, and evapotranspiration have been identified as drivers of the hydrogeologic system on barrier islands. Numerical models have been utilized to represent groundwater flow on these barrier-marsh systems. However, the parameterization requirements of these models may fail to resolve the nuance associated with fine scale geology observed in these environments.

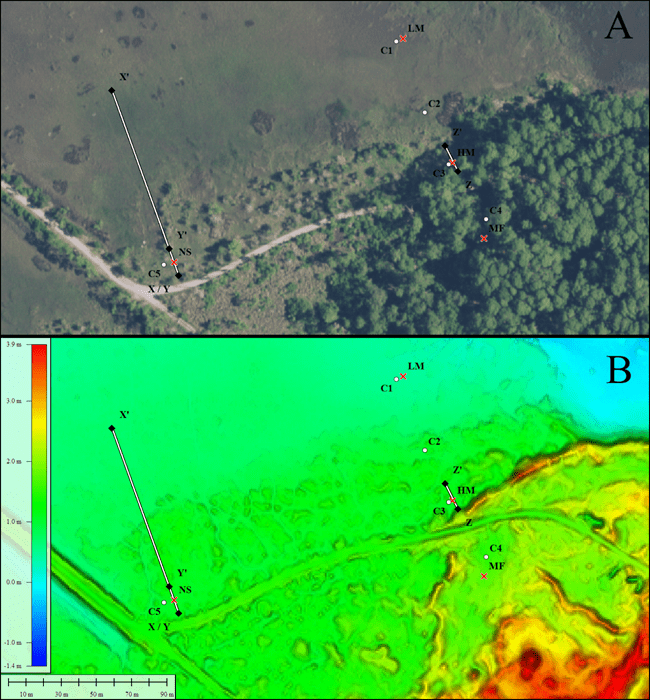

We set out in August of 2020 to attempt to characterize these hydrogeologic nuances using a variety of techniques, some conventional, and some more novel in this environment. One more novel method was the use of electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) to create a timeseries spanning the transition from maritime forest to saltmarsh. This was able to map the mixing zones of groundwater within the sediment and identify sediment types that allowed freshwaters from the island to penetrate the muddy saltmarsh platform. To assist with the interpretation of the ERT, five vibracores were retrieved adjacent to survey transects and analyzed at 10- and 15-cm intervals for sediment characteristics including laser grain size analysis. A timeseries record of water table elevation and salinity was collected along a transect spanning the entire ecotone shift from low marsh to forest. Finally, ensemble empirical mode decomposition was used to identify hydrogeologic drivers such as tides and precipitation from the complex water table signal, a novel use of this method which had been otherwise used for surface waters.

Four years later the study concluded, elucidating the processes which create the dynamic environments along the maritime forest-saltmarsh transition, in addition to highlighting the vulnerability of barrier island systems to shifts in the hydrologic regime. Freshwaters on the island recharges rapidly with precipitation events suggesting a vulnerability to salinization of the surficial aquifer during saltwater flooding. Large tides were observed driving saline groundwaters through the marsh platform all the way to the base of the maritime forest during lunar syzygy. While not viable for determining the salinity of groundwaters, ERT was useful for the mapping of hydrogeologic units of different porosity and observing freshwaters entering the marsh platform following precipitation events. Our geologic analyses of sediments reinforced the notion that the stratigraphy of the saltmarsh is complex and spatially variable. One exciting result of the analysis was that ensemble empirical mode decomposition was able to discern the key hydrologic drivers from the water table signal. Contributions to the observed signal from precipitation events and tidal forcing were able to be quantified at each well along the study transect.

Waties Island, as with many barrier islands, faces an uncertain future. Shifts in the hydrologic cycle such as higher sea levels, increased precipitation, and more frequent hurricanes threaten to alter the hydrogeologic balance. Saltwater intrusion and aquifer salinization may radically shift ecological baselines on short timescales, which would jeopardize the overall stability of the island. It is crucial to further characterize and understand the physical and geologic processes controlling groundwater mixing between the barrier island and saltmarsh to ensure the resilience of these systems in an uncertain climate future.