Contributed by Danielle Peltier, GSA Science Communication Fellow

On 9 December 2024 at 1:72 a.m., a magnitude 3 earthquake impacted New Madrid, Missouri, USA. For folks in western states, this isn’t newsworthy. California had 16 magnitude 3 earthquakes over the same week. So why do low-magnitude earthquakes in the Midwest lead to flashy headlines and eye-catching social media videos warning that “the next big one” or a “doomsday earthquake” is imminent? And if you live in the Midwest, should you be worried? The answer is complicated, so let’s break it down.

What Causes an Earthquake

Earthquakes are primarily caused by faults, or fractures in the Earth’s crust. Forces like the weight of things on the surface and the movement of Earth’s tectonic plates are always impacting the layers of rock that make up the crust. These combined forces are called stress and can build up to the point that the rocks break. This creates a fault, and the sudden release of stored energy during this process is what we feel as an earthquake. The magnitude of an earthquake is based on the area of the fault, how much the fault moves, and the rock’s properties, like its strength and brittleness. Since stronger rocks can accumulate more stress, it takes longer for the rock to break but a greater amount of stored energy is released creating stronger earthquakes that are less frequent. Conversely, weaker rocks can’t accumulate as much stress and will have more frequent, low magnitude earthquakes.

Faulting and earthquakes have occurred throughout Earth’s history, creating countless faults across the entire surface. Earthquakes often occur along existing faults—like the San Andreas Fault in California—because once something is broken, it’s more likely to break in the same spot. Now this doesn’t mean every fault is always at risk for earthquakes. Most faults are inactive because their stress state remains constant. Faults reactivate when there is a change to their stress state, either by the addition or reduction of stress on the fault.

The New Madrid Seismic Zone

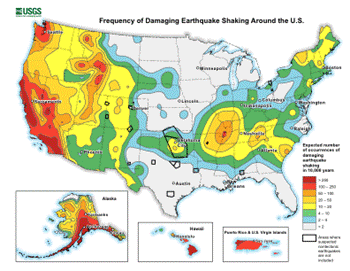

Most earthquakes in the Midwest occur in the New Madrid Seismic Zone (NMSZ), which lies in the Mississippi River Valley and spans northeastern Arkansas, southeastern Missouri, western Tennessee, western Kentucky, and southern Illinois. Although the NMSZ receives the most attention in news and media, it is one of three seismic zones located in the Midwest.

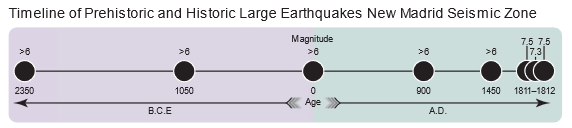

The faults responsible for the earthquakes formed during the Cambrian Period between 538.8 and 485.4 million years ago, but NMSZ quakes only started within the last hundred thousand years. Geologists can identify previous earthquakes in the rock record by identifying features related to liquefaction—when the shaking causes soil to act like liquid—and sand volcanoes—when the liquified soils and water erupt from the surface. The size and epicenter of an ancient quake can be estimated by correlating these features across an area. There are eight large earthquakes, with magnitudes of < 7, known to have happen in the NMSZ.

A series of three magnitude 7–7.5 earthquakes from December 1811 to February 1812 were the most recent large events, and the shaking was felt across the eastern U.S. The quakes and associated hazards like landslides caused substantial damage to the region. There are even tales noting how the shaking caused the Mississippi River to flow backwards. Now, it’s unlikely the flow direction Mississippi River actually changed, but the quakes did modify the topography of the area and would make flowing water appear to change course. Since then, no NMSZ earthquake has surpassed a 7 magnitude.

Is the “Big One” Coming?

I spoke with Dr. Elizabeth Sherrill, a geophysicist that specializes in earthquakes, to get her take on the whether the “big one” is coming to the Midwest. In short: we really don’t know, but a great earthquake (magnitude 8+) is unlikely. The cause of these earthquakes is not fully understood, which makes it difficult to make predictions. There are two leading theories as to why this area experiences earthquakes. The first is glacier pressure release. Over the last 1.8 million years, there were cycles of glaciers advancing into the Midwest then retreating north. The immense weight of these glaciers compressed the Earth’s crust, and when they melted, the crust rebounded upward. You can think of it like a bed: your body leaves an imprint while you sleep, but over time, the mattress returns to its original shape. Similarly, the Earth’s crust rebounds after glaciers retreat, which can change the stress state of the underlying faults. The second is the influence of far-field stresses. Just like the pain from hitting your elbow can radiate down to your hand, stresses from large-scale tectonic plate movements can travel through the Earth’s crust. These far-field stresses can gradually build up or redistribute stress on inactive faults and eventually cause an earthquake. It’s likely that both processes contribute to midwestern earthquake potential, which makes it difficult to understand how much stress is building up and predict how it will be released.

According to the USGS, there is a 25–40% chance the NMSZ will experience a magnitude 6.0 and greater earthquake in the next 50 years. However, the magnitude isn’t the sole determinator of how damaging an earthquake can be. Midwestern infrastructure and architecture is designed with more frequent natural hazards, like tornados, in mind. This means a magnitude 6 quake can have a greater impact in Missouri then somewhere like California. To assess the potential impacts of larger earthquakes in the Midwest, Dr. Sherrill and her colleagues conducted loss models that estimate the extent and cost of damages. They found that a magnitude 7.6 earthquake in the NMSZ could cause losses exceeding $43 billion (adjusted for 2024 inflation).

“Not all natural hazards have to be a natural disaster, and there’s a lot we can do to mitigate the risk,” says Dr. Sherrill. Scientific funding is crucial to prevent natural disasters, according to Dr. Sherrill. She continues, “The more we know, the better we can prepare.” Any potential earthquake can be scary, but a doomsday scenario is highly unlikely. You can keep yourself and those close to you safe by understanding your risk and staying informed. In the case of an earthquake, it’s important to remember safety precautions:

- Stop what you’re doing.

- Drop to your hands and knees.

- Cover your head and neck under a sturdy desk or table or your arm.

Despite what you may have heard, do not seek shelter under a door frame. You can visit the USGS Earthquake Hazards Program website for more information on earthquakes, hazards, and precautions.

References Cited

Tuttle et al., 2019, Evidence for Large New Madrid Earthquakes about A.D. 0 and 1050 B.C., Central United States: Seismological Research Letters, v. 90, no. 3, https://doi.org/10.1785/0220180371.